The Exhibition

The exhibition outlines the philosophical and technological context of the time in which Leonardo da Vinci lived in order to explore his study of the forms and processes of the Plant world in greater depth, through his eyes as a “systemic” thinker, highlighting the connections between art, science and nature and the relationships between the different spheres of knowledge.

The botany of Leonardo thus becomes a privileged perspective to open up modern conversation on scientific evolution and ecological sustainability.

From phyllotaxis to dendrochronology, Leonardo’s writings and illustrations capture prominent insights in the history of botany that arose from his keen powers of observation an d experimental spirit. They map out a dynamic vision of science that is inseparable from art and technology, and is still highly relevant and applicable today.

Natural elements and interactive installations are interwoven among the original pages. The exhibition offers the public the chance to learn more about an important area of Leonardo’s study and appreciate the outstanding results.

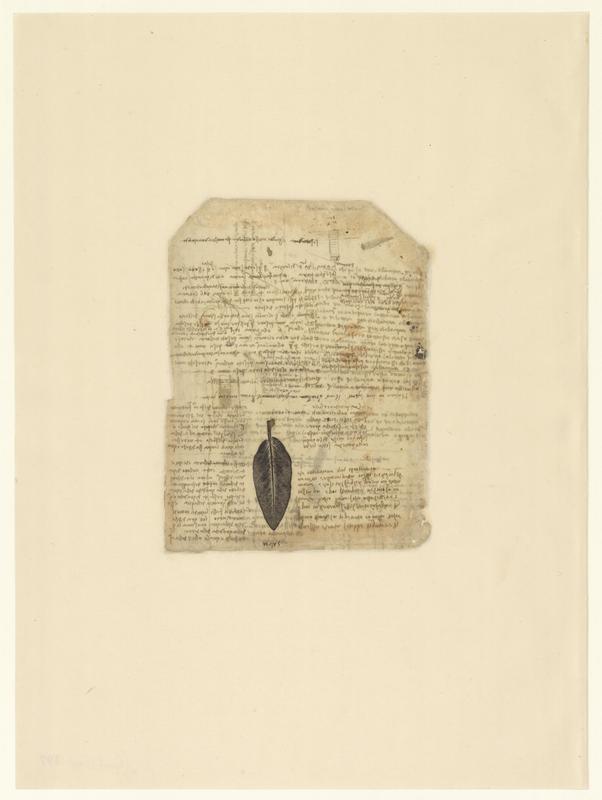

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Codex Atlanticus, folio 197 verso. Method for making a “positive” print; bottom, a sage leaf printed in negative. Copyright Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana/Mondadori Portfolio.

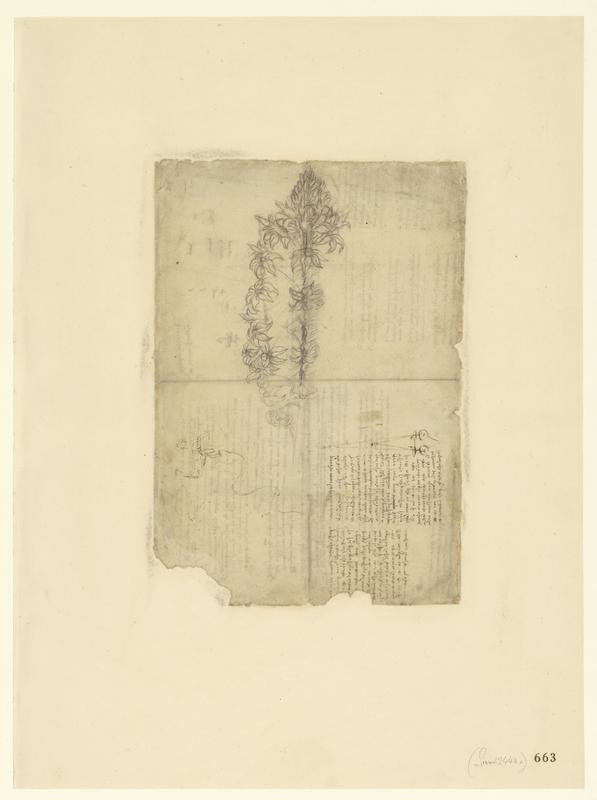

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Codex Atlanticus, folio 663 recto. Floral composition; note on the usefulness of glasses. Copyright Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana/Mondadori Portfolio.

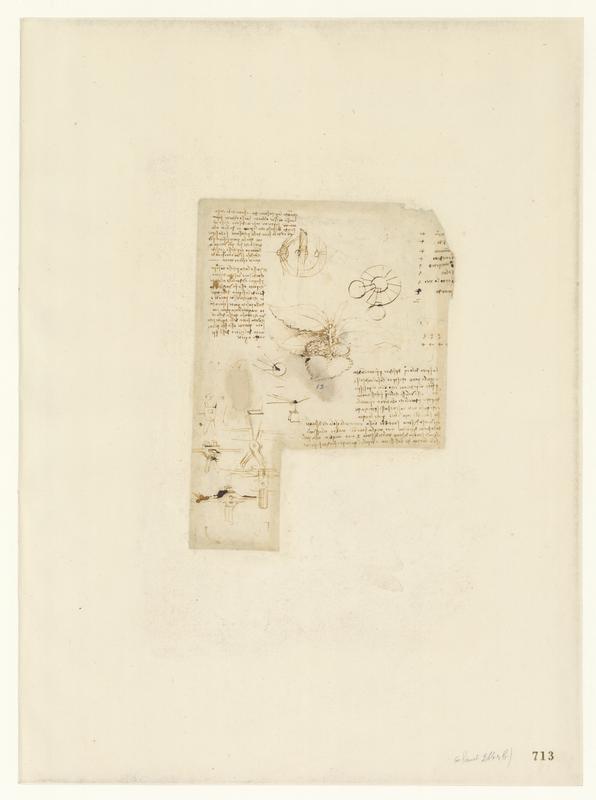

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Codex Atlanticus, folio 713 recto. Centre, leaves and fruit; top right, the names of eight people; left, study of the effects of percussion on elastic and non-elastic objects; right, note on the sphercity of water (the element); bottom, inclined plane and model of a pincer joint. Copyright Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana/Mondadori Portofolio.

The Dodecahedron and the Mulberry Tree

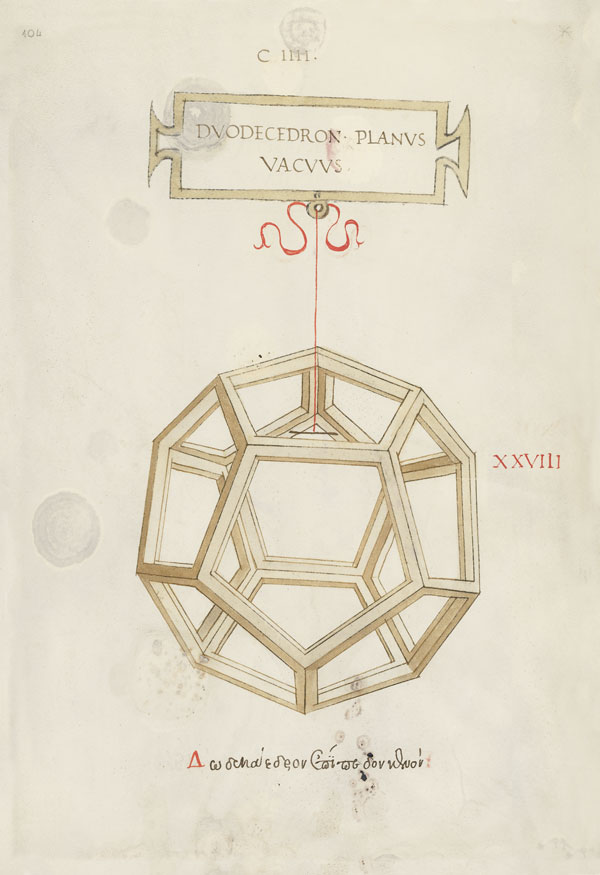

The geometric form of the Dodecahedron and the Mulberry tree are the two symbols of the exhibition.

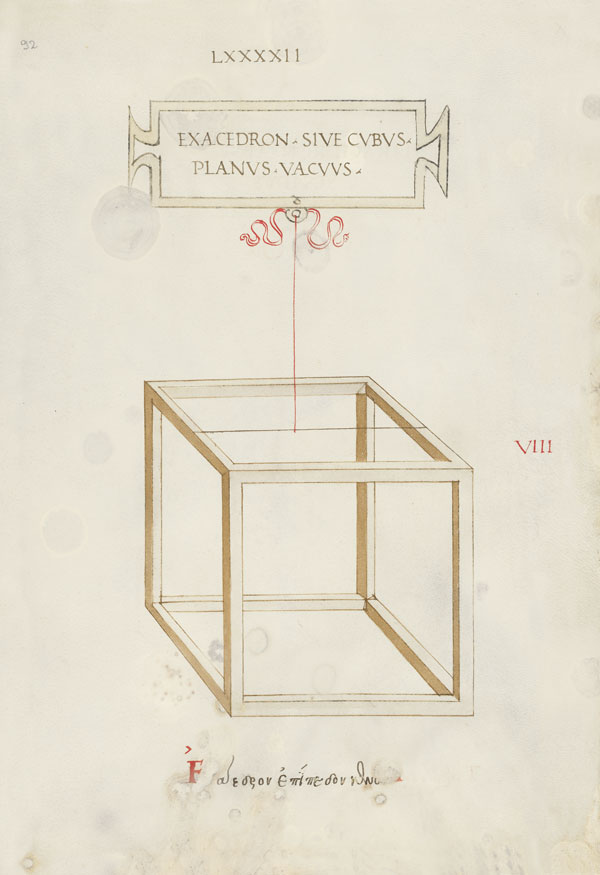

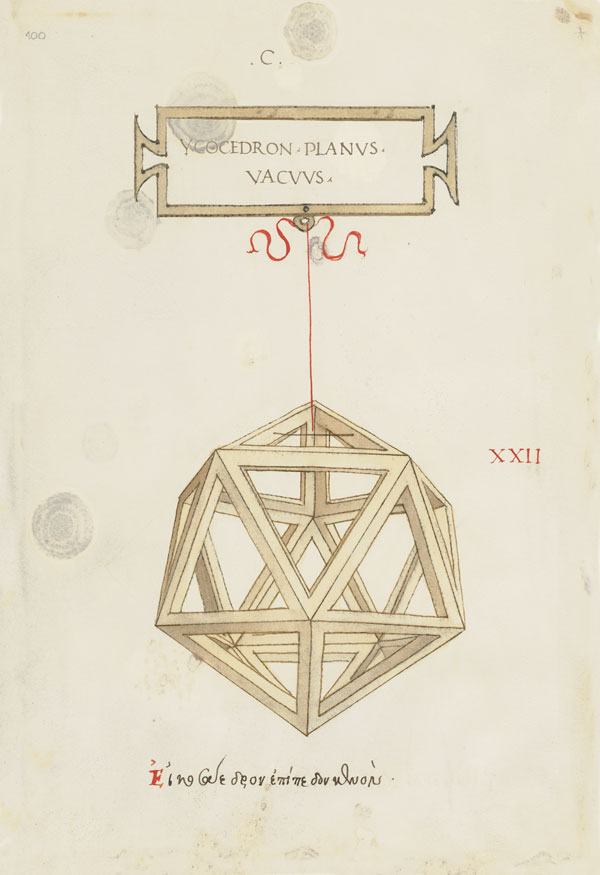

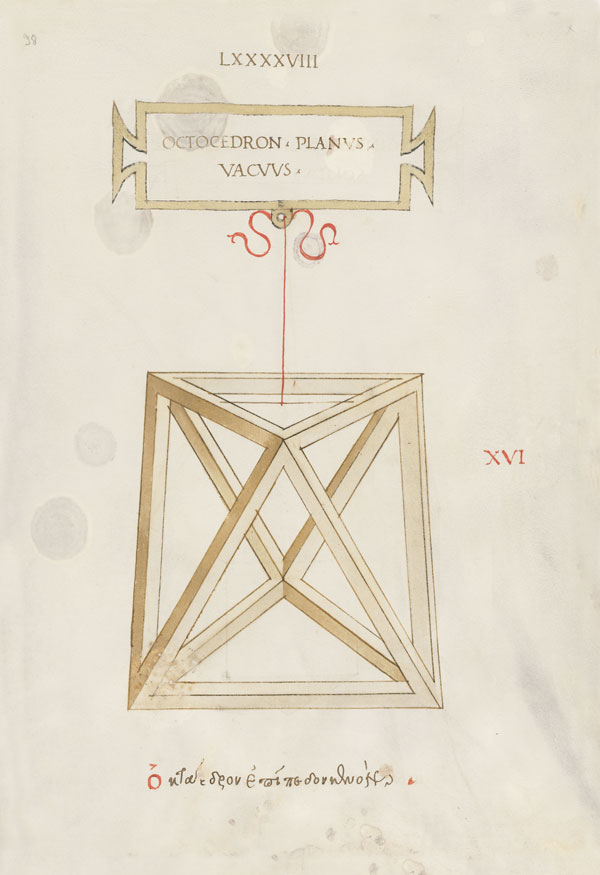

For the ancient Greeks and Renaissance Neoplatonists, the Dodecahedron represented the entire universe, while the other Platonic polyhedra represented the four elements: earth (the cube), air (the octahedron), water (the icosahedron) and fire (the tetrahedron). Leonardo designed the polyhedra for Luca Pacioli’s manuscript De Divina Proportione. He admired the shapes with which nature created and transformed matter, reflecting on the way that man, a part of this creation, can interpret and reinterpret it. For Leonardo, the interconnectedness between the three worlds that make up the universe – vegetal, animal and mineral – was a mystery to be revealed but not violated.

The Dodecahedron and the Mulberry tree encapsulate one of the main themes of the exhibition, introducing Leonardo’s systemic vision of the world to the general public. After five centuries, his perspective offers us an invaluable opportunity to observe, interpret and reinterpret the world of today, interweaving the systemic thinking he suggested five hundred years ago with the knowledge and technology now available to us (including the -omic sciences, mathematics and bioinformatics). Taking Leonardo as a model for our immediate future involves imagining a new vision of the world, and a different understanding of the role of humans within it. One of the aims that we should be setting ourselves is certainly to find new ways to reduce the artificial nature of progress (today caused mainly by non-biodegradable chemical substances that are not part of the ecosystem) and study how to defend ourselves from the impending threat that the epigenetic influx of genetically modified organisms bring with them.

Drawing from Leonardo in an authentic and yet contemporary way also means trying to define a new way of thinking that considers the events in Florence starting from the beginning of the 15th Century and makes them relevant today. A period in which, under the patronage of the Medici, alchemy and Neoplatonic thought embraced and nurtured the arts, technology and science in an organic vision that was at once both highly cohesive and incredibly diverse.

The polyhedra

In the Grand Cloister of Santa Maria Novella as well as a number of other piazzas around Florence, 5 solid geometric shapes are on display that according to Plato (428-347 B.C.), building on Pythagorean ideas, gave form to the four elements of the cosmos:

- the hexahedron for the land

- the icosahedron for water

- the octahedron for the air

- the tetrahedron for fire

And then there was the dodecahedron, a sublime synthesis of the quintessence:

“there remained one construction, the fifth; and the god used it for the universe” (Plato’s Timaeus).

Leonardo began his study of mathematics and geometry in Milan thanks to the acquaintance he made with Fra Luca Pacioli (1445-1517) at the court of Ludovico il Moro in Milan. He designed sixty regular solid shapes for Pacioli’s Compendio de la divina proportione and in exchange received invaluable insights. Thanks to this productive acquaintance, over the years Leonardo developed profound insights into arithmetic, Euclidean geometry, proportion and the founding elements of the cosmos, nature, science and art.

Pictures from De divina proportione, ms 210, Bibliothèque de Genève